Chapter

1

FISHERFOLK

Fisherfolk have always been a unique breed of people. Living constantly in the shadow of a tragedy, a wife or a mother as she bids farewell to her loved ones leaving for a fishing trip has the secret fear that she may never see them again. The fatality rate is very high in comparison with other industries.

Baiting times at Buchanhaven, Peterhead

(Picture: North of Scotland Library Services.)

Around the beginning of the century, the fishermen usually lived in parts of their towns near the seafront. Houses were made of granite and often had wooden floors. In the living room would be the range-fire with a stool extending across the whole front of the range. Built into one wall would be the "Box-bed", which was a bed with three sides covered in, hence the name. This arrangement made the resting place warm and comfortable. At the rear of the dwelling was the part which contained the wash-tub and wringer. Nets were often mended in the garret upstairs or in some cases in an outhouse. In fine days during the summer, mending would be done outside.

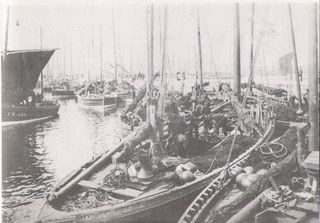

Sailboats in Fraserburgh harbour

(Picture: St. Andrews University)

Some of the fishermen used lines to catch fish. These lines were baited with mussels which were gathered from the seashore at a place known as the scaup. This was mainly the task of the females, while the male members went to sea. Whenever they reached a suitable age, the females would learn to mend nets, go to the scaup for mussels, to sheel and bait the lines.

Landing the catch from a sailboat

(Picture: St. Andrews University)

The staple diet of fishermen was plain foods, consisting of porridge and soups, with vegetable broth a speciality. Saturday dinner was salt herring and tattie time. The herring would be cured in a small barrel at the summer season with another barrel cured at the East Anglian fishing. Also on their menu would be dried fish, either ling or tusk. These fish would be cleaned, split down the front, salted and dried on the rocks.

In some cases church attendance was regular, each family going to their respective church. Every household had its own seat in the place of worship and parents would really feel proud going to church as a whole family. For church the men would wear dark navy suits, while the women wore dresses down to the calves of their legs. After the service, especially during the summer, the family would go for a short walk, but whenever they arrived home their Sunday clothes were exchanged for more casual dress. The Sunday clothes were also the attire worn at funerals, which were occasions of great mourning. When a disaster took place at sea, it would be a time of deep sorrow, whole communities lamented the loss of an individual or an entire crew.

Weddings amongst fisherfolk were times of rejoicing. In the earlier part of this century, a young fisherman usually chose for his bride a lass from a 'fisher' family, knowing that she would have a first-hand idea of the hardships he faced. Another reason being that she would have learned to mend nets, a great asset to any fisherman who owned gear.

Sea-going men wore thick underwear, often knitted at home. Their trousers would be made of a strong material, which gave them the name of "Hairback Troosers". The home knitted "Faroe Jersies" were famous and kept them warm in low temperatures. Oilskins which stretched down to the knees had high necks. On every head was perched the well known "Sou-wester", which had a small peak at the front and a longer one at the back. Sea boots to the thighs were essential. Women when gutting the herring wore an oilskin frock known as a "Quite", this reached almost to the ankles. Rubber boots were supplied by the employer who was a curer. The head was covered by a scarf. Each of the fingers would have "Cloots" tied around it for protection from the sharp knives used to gut. These women worked at an astonishing speed.

Hauling nets aboard a steam drifter.

(Picture: St. Andrews University)

A herring drifter

crew consisted of 9 or 10 men including skipper-mate, five deckhands, cook and

two engineers known as the "black squad". Life on deck was very hard. Seventy or eighty

nets had to be pulled in all kinds of weather. It would be very difficult to

get the nets aboard if the wind changed direction after the nets were laid.

When the nets were on board, if the catch was reasonable, the nets had to be

"red up" that is cleaned. This was a task that was performed with

extreme caution, as it was undertaken when the drifter was steaming at top speed

towards port in order to obtain the highest price for the fish. Since the deck

crew were paid on a share basis, every minute counted in getting the catch

ready for sale. In charge of the engine room was the "driver" who

kept the steam engine going full speed. The fireman was kept very busy stoking

the boiler with coal. During hauling operations, if the catch was good, the

engineer could "scum" the herring that dropped out of the nets. In doing

so he earned what was known as "stoker", which was shared between

himself, the fireman and the cook. The fireman also took his turn out of the

engine room during the time the boat was fishing. His task was to coil the

leader rope on to which the nets were tied. This was a very monotonous job,

lasting hours on end and it took place in a small locker room in the fore part

of the vessel.

Early steam drifters and sailboats in Lowestoft harbour. (Picture: St. Andrews University) The 1914-18 war had just finished and men

were coming home to their ordinary way of life. Fishermen were returning

from the Royal Naval Reserve Patrol to take up their work which had been

interrupted by the call to arms. Steam drifters were

replacing the sailing boats, some of which had been fitted with engines.

Mechanical propulsion brought increased mobility and men travelled long

distances following the herring around Gutting scene during the herring season. (Picture: Mrs.Jack, from the Jack collection via St. Andrews University) For a few months

during the first part of the year the most frequented port was Stornoway on the

Isle of Lewis, off the west coast of to gut and pack

the lovely large fish. There was also a base at Stronsay in Orkney. The months

of June till September saw the fish move to an area which could be reached by

boats from Wick, the It was among the

fisher-folk living and working in such conditions and circumstances that God

moved in power during the later months of 1921. A Scottish fish-wife

with her baskets. (Picture: J. Slater Portsoy)

Cooking for nine or ten men was no easy task. As the nets were hauled in the cook's job was to pull in

the "sol-rope" which was the lower part of the net. After the nets

were aboard the crew had to be fed. Every second morning he would clean three

dozen fresh herring and fry them for breakfast. Cooking was done in the galley

on a coal-fired stove and space was limited. Three of the crew members were

paid a weekly wage. The engineer received around £1 10s (£1.50), the fireman

around £1 5s (£1.25) and the same for the cook. On top of this was the sum

received for the herring mentioned before which provided these three men with

"stoker".